A Conversation with Anne Liu Kellor, Part 2

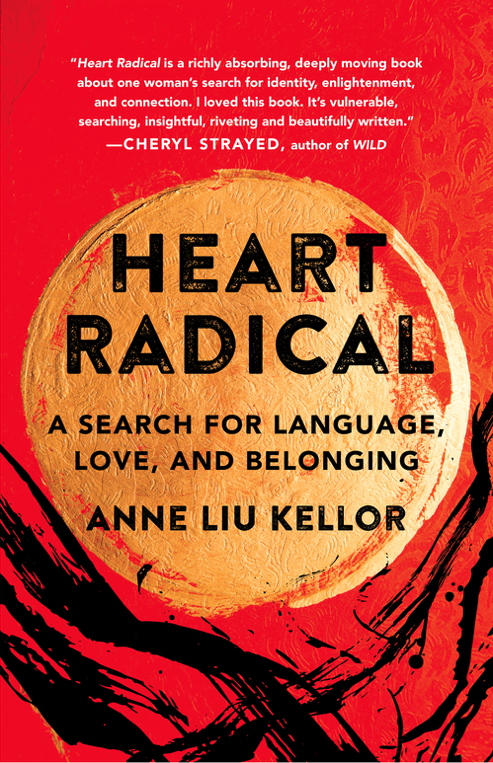

In our last post, we featured the first half of our conversation with Anne Liu Kellor. She spoke about her new memoir, Heart Radical: A Search for Language, Love, and Belonging, and what brought her to write her book. Now please join us as we talk agnostic Buddhism, the power of relationships abroad, and the challenges and opportunities about writing from your life.

Undomesticated: Your thoughts on Tibet and Tibetan Buddhism show how it’s become a cause celèbre. You call that out and feel disconnected from it because of the appropriation issue. Have you been able to reconnect to Buddhism in the decades since you left China? Are you still involved in Tibetan activism?

Liu Kellor: I love that you asked that. I have continued to essentially consider myself Buddhist, although I’ve adopted the term agnostic Buddhist because I don’t necessarily know or believe everything that Buddhism espouses and that’s why I especially struggled with some of the elements of Tibetan Buddhism. So I’m more of a Zen Buddhist, I would say. With that said, though, I never fully entered into Buddhist communities or was fully comfortable adopting that identity. But more than any philosophy out there, Buddhism informs the way I see and live life the most, of course combined with other influences. That whole spiritual thread of the memoir was difficult for me to do justice to while staying focused on that timeframe of my twenties, so it’s where some of my work continues to lean into. In the years that followed my return from China, I continued to ask myself about my connection to Buddhism and to Tibet. Part of me felt guilty or hypocritical that I could be so invested and feel so much connection to the people and the cause, and then leave it because I’m not involved with the Tibetan rights movement now.

I think what I’ve come to accept and understand about myself and the world is how interconnected everything is when it comes to any work that aims to foster compassion, personal growth, human rights, and justice. So my focus has shifted, especially in recent years, more towards what’s happening in America right now and in our history. But there was something really integral for me about learning from the story of Tibet and China, from the teachings of the Dalai Lama, and from the spirit of the people that informs their struggle.

The Tibetan people and culture suffered greatly under Chinese communist rule, and yet the Dalai Lama continued to preach compassion for their oppressors. Looking through the lens of empathy, I cannot help but see how ordinary Chinese people suffered so much during this era too, especially during the Cultural Revolution where so many temples, documents, artifacts—and so much trust between people—was destroyed.

Children turned in their own parents. People learned to distrust everyone. Everyone was afraid for their lives and carried out orders out of a deeply programmed human drive for self-preservation. I say this not to lessen the extreme cruelties that Tibetans were subjected to, but to highlight the way that we can hold others accountable, at the same time that we can seek to not let our hearts harden in hatred against an entire group of people. We can see how everyone is responding to karma—to an undying chain of cause and effect—and how forces of history and collective trauma have created the capacity for such cruelty in human beings. This deeply affected how I came to question my purpose in life and how I can give back more to others.

Anne Liu Kellor and Tibetan friends.

Undomesticated: You do that really well and I also think you do continue this in your book because you write about it and that is a lasting gift to us. People will read about it now, a few years from now, and later, and it will still be there so I think that makes that part of your life continue, which is the power of writing. Speaking of powerful writing, your former boyfriend Yizhong is such a central part of your story and your relationship with him is such a positive one that we can all learn from when it comes to communication. Do you think your immersion would have been as successful if you hadn’t been in a romantic relationship in China? Can we ever truly learn about a place if we aren’t so intimately involved, in all aspects of that word?

Liu Kellor: I think having intimate friendships, whether they are platonic or romantic, is the key to learning about a culture because then it becomes not just this academic study or this mass of nameless people. Instead, it becomes about individuals who you deeply care about and who help you go beyond certain assumptions or stereotypes that you might have had yet not realized if you didn’t get to know people on an up-close human level. So I’m grateful that I was able to have that kind of intimate relationship for there’s no way I would have otherwise gotten to know not just China but also locals in the same way. Being with someone who was so accepting of me also helped me relax into the language and feel how it lived in me, as opposed to always speaking it through this lens of a foreigner and feeling myself digested as “the other'' or as a cultural ambassador in some way.

Undomesticated: And his parents played a big part in that, too. They seemed lovely and were so accepting.

Liu Kellor: Yeah, and that still makes me sad that I left so abruptly. When I set out, I didn’t want to be one of those, quote unquote, foreigners who come and have their China adventure and then leave. I thought my life was going to be tied to working in China, and that I would always be going back and forth and it didn’t turn out that way. But in other ways the culture and the language lives on in me and that can’t ever be taken away.

Undomesticated: Have you returned to China since you left almost 20 years ago? If you have, can you talk a little about how it felt to return. And if you haven’t, what has kept you from going and if you plan on visiting in the future, what do you most look forward to seeing or experiencing?

Liu Kellor: No, I haven’t been back to China, but I did go with my family to Taiwan and that wasn’t until 2019. Initially I thought I’d be back in a couple years and maybe live in Shanghai or some more international city. But then I got married and had a kid, and my life became way more about being rooted in the Pacific Northwest, connected to nature and to writing.

But the main reason it took me so long to return to anywhere in Asia was motherhood and finances, and a stressful marriage. It just never seemed like the right time and I wanted to wait until my son was a little older, so he could come with me. I think I also got spoiled from my youth in thinking that I needed a longer period of time in order to make it worthwhile to go all that way, which of course is the ideal.

But after finally taking that two-week trip to Taiwan in 2019 with my son and my now ex-husband Matthew, I realized that two weeks is still amazing if I can make it happen and I’m not going to wait that long again.

Going back to Taiwan ignited that same feeling of hearing Mandarin and remembering again how it’s a part of me. It’s still very accessible to me even though I don’t speak Chinese very much now because I don’t have a Mandarin speaking community that I belong to, except for my mother and her friends. But it still comes back quickly, which was a relief to realize that I can still access some of that hard-earned vocabulary that I learned while I was in China itself. Somehow it sticks, it’s there. Even if my character study has fallen by the wayside, I trust now that I will always be able to communicate in Chinese. And going back reminded me of how much I crave returning to that old part of me that speaks and lives primarily in Chinese, as well as how much I value how any kind of travel opens us to spontaneity and catapults us outside our comfortable identities and lives.

Undomesticated: Did you visit relatives there or was it purely for leisure?

Liu Kellor: We were going to visit my uncle, and then he ended up being ill so we didn’t get to see him. A big part of the trip was about finally being able to introduce my son to international travel, to life outside of America, and to the feeling of being in a bustling Asian metropolis—a place where white faces do not dominate the landscape. Yes, he loved riding the trains, as well as sampling new foods and night markets, but most significant to me was wanting him to see and hear me speaking in Mandarin and thus to know me in that way, as well. Because as a blond-haired, blue-eyed, one-quarter Chinese mixed kid, he’s going to grow up with the world reflecting back to him that he is white and that he’s not Chinese and so those connections become even more nebulous unless they’re really cultivated.

Undomesticated: Did you go all around Taiwan?

Liu Kellor: Yes, we started in Taipei and went down the east coast and stayed with friends in Hualien. Then we went to Tainan because my mom went to college there. I’d love to go back to the east coast and plant myself in one of the smaller artist-community towns and do a writing retreat on my own.

Undomesticated: That sounds so great! Can you talk a little about your writing process? Your story takes place a couple decades ago, yet it seems timeless in so many ways. When did you decide to write this story, what was the process of getting to the point where you could be so honest about those events and with yourself?

Liu Kellor: This book was a haul! I’ve long considered myself a writer and wrote a ton in my journal during both of my trips to China. I eventually started to form essays and knew I had a book in me, but didn’t know what that was. For a long time I thought that it needed to be more outward looking, that it couldn’t just be about me, that I needed to research things and become a semi-expert on something. But as time went on, I came back to the States and got my master of fine arts degree, and it was clear I was writing a memoir. But it was still a challenge because I was writing mostly standalone essays at the time. And while I do consider myself more of an essayist, since so many of my pieces were focusing on this China journey, the book naturally led to a more traditional story arc.

It seemed like most of the story was there, that there were “just” some missing connective details that I called bridge pieces. So I thought I’d just write those bridge pieces to cobble it together, but that didn’t prove so easy. Those so-called bridge pieces were not very good and then as time went on, because I was still so close to the experiences and still living out the meaning of it, the ending kept moving and there was no easy singular lesson to impart. Also, as I mentioned earlier, some of the deeper questions informing my life’s journey have revealed themselves over decades.

It took me so long to finally find a publisher, which in part relates to external factors and to the competitiveness of the industry, but looking back, I can also say that this was an internal thing where I needed to understand more deeply what it was that I wanted to say with this book. What I couldn’t access yet or what threads remained not fully digested to be carried out in my future. As you keep living, your lens on your story keeps changing. So I finally changed it to present tense to lock it in time so that I couldn’t continue to alter my perspective. Ultimately, I think we have the ability to write about the same time period of our lives through many different vantage points—which in turn can create completely different books. I finally had to accept that this is the version that has come to live on the page, that chronicles my younger self, and there’s still more interpretations to come.

Undomesticated: What are you writing next?

Liu Kellor: I have completed a collection of essays called “Uncertainty, Trust, and the Present Moment: Essays From In Between” and it explores a lot of the same themes of identity, race, intergenerational inheritance, self-compassion, and impermanence. A few pieces were born out of outtakes from my memoir but most of them I’ve been called to write over the last decade. I also have another book that’s an intergenerational memoir about marriage, inheritance, and the meaning we invest in our homes and our things. That’s on hold for now, but it’s another book I’ve worked on for a long time.

Undomesticated: That sounds really great! I look forward to reading those books and thank you so much for speaking with me today.

Liu Kellor: Thank you! It was my pleasure.

For more on Anne Liu Kellor or her book Heart Radical: A Search for Language, Love, and Belonging, visit anneliukellor.com.